Gender Beyond the Binary

You surely know that women and men differ, on average, in certain ways – in the way they behave, and in what they prefer to do for a living or in their spare time. There are also differences, typically much smaller ones, in the cognitive and emotional abilities of women and men, and girls and boys. Within the binary framework, these differences are often perceived in absolute terms – women are like this, men are like that – both at the level of single characteristics (e.g., spatial skills) and human ‘nature’, as in Men from Mars, Women from Venus. This post describes a different framework – the mosaic hypothesis – for thinking about variability in human psychological characteristics, according to which humans possess unique combinations (mosaics) of gendered characteristics, some more common in women than in men, and others more common in men compared to women (Joel, 2011).

Overlap

Gender differences are often discussed in binary terms, yet in reality, no gender difference can be described in this way. Rather, there is some degree of overlap between women and men even on psychological variables that show very large gender differences, such as sexual attraction and extreme physical aggression. Thus, many more women than men are sexually attracted to men, but this doesn't mean that all women are attracted to men and all men are not. Nor does it mean that all women are more attracted to men than all of the men are (for example, lesbian women are less attracted to men than gay men are). Similarly, women and men differ, on average, in the tendency to be extremely physically aggressive, but this doesn't mean that all men are physically aggressive or that all women are not. In fact, most women and most men are not physically aggressive. The difference between the genders on the group level reflects the fact that within the small group of individuals who may become highly physically aggressive, most are men.

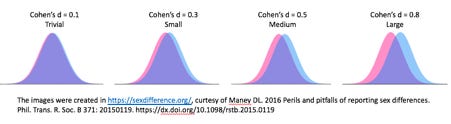

Gender differences are based on comparisons between averages – the average scores for groups of women and men. A statistical measure called ‘Cohen's d’ (which is the difference between the means of the two groups divided by the pooled standard deviation) is commonly used to describe to what extent groups differ from one another. The convention in psychology is that differences with a "Cohen’s d" of 0.1 or smaller are considered trivial or negligible; those with a "Cohen’s d" of around 0.3 are considered small; around 0.5 would be medium; and, around 0.8 or more, large. To get a better sense of the meaning of Cohen’s d, the Cohen’s d of the gender difference in height in the USA is ~1.7.

Dozens of thousands of scientific papers reporting on gender differences in psychology have been published in the past century. Several reviews of these studies concluded that for most psychological measures – including those related to personality, as well as cognitive and emotional abilities – these differences are mostly trivial. For most other variables, they are small or medium. Only a few variables – such as physical aggression, occupational preferences, sexual attraction to men or women, and gender identity – show large or very large gender differences (Hyde, 2005; Hyde et al., 2018; Zell et al., 2015). This is also true of gender differences in children. There are hardly any behavioral and psychological differences between girls and boys in the first two years of life, and the differences that do emerge later are typically small to medium (Eliot, 2009).

It is worth noting that gender differences vary across time and culture. For example, in the 19th century most teachers in public schools were male, whereas nowadays most teachers are females. Similarly, there were very few female university students in the 19th century, but nowadays female students outnumber male students at all levels of academic studies. However, this is not true everywhere. For example, in Afghanistan, the vast majority of students are male. Clearly, these differences across time and space reflect differences in gender norms. The fact that culture has such an impact on gender differences ties in with the question you may have already asked yourself: are gender differences a result of nature or nurture, that is, of biological or environmental factors? (You can read about this question in my next post.)

Mosaicism

But in my studies, I was interested in another question: do gender differences in psychological characteristics add up in individuals to create two types of humans, women and men. We found that they do not. Instead, the vast majority of humans possess both feminine (more common in women compared to men) and masculine characteristics. You, yourself, may be aware of having certain feminine characteristics and certain masculine ones (you can explore your own mosaic of gender characteristics and see how it changes when your answers are compared to those of people around the world, by filling out the Gender Mosaic Questionnaire). But did you know that all human beings probably have a mix of traits, each person having them in a unique combination?

Researchers who launched the first modern studies into masculinity and femininity in the first half of the 20th century assumed that there existed distinct personalities – one characteristic of men and another, of women (Terman & Miles, 1936). In reality, already back then, their studies found that people could be masculine on some sub-scales – for instance, those covering hobbies, interests or reading preferences – and feminine on others – for example, general knowledge, personality characteristics or attitudes. These results were ignored, however, in favor of the view that women and men are aligned along a femininity-masculinity continuum.

In the 1990’s, American psychologist Janet Spence rediscovered the idea that “men and women do not exhibit all of the attributes, interests, attitudes, roles and behaviors expected of their sex according to their society’s descriptive and prescriptive stereotypes but only some of them. They may also display some of the characteristics and behaviors associated with the other sex” (Spence, 1993). Studies by other researchers provided further support for this idea, showing that two variables on which women and men differ significantly, on average, are not necessarily well-correlated. For example, if a woman scores high on empathizing (the ability to understand how someone else feels, on which women score on average higher compared to men), this doesn’t necessarily mean that she scores low on systemizing (the drive to analyze or construct systems, which is more common in men) (Greenberg, et al., 2018). Another such pair is interest in people and interest in things. Researchers often stress the large difference between women and men on these preferences but rarely discuss the low correlation between the two – that is, the fact that people may, for example, show a high interest in both people and things, or a low interest in both (Tay et al., 2011).

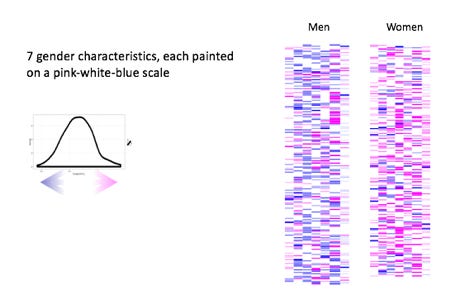

Finally, in 2015, my colleagues and I conducted a large study that analyzed the behaviors, preferences and attitudes of over 5,500 individuals from three datasets (Joel et al., 2015). We analyzed only variables that showed a large difference between women and men. For each of these variables, we defined a range of ‘feminine’ scores – that is, those that were more common in women than in men – (pink in the figure below), a range of masculine scores (blue), and a neutral range, that is, scores similarly common in women and men (white). With these definitions we found very few people who had only feminine or only masculine characteristics. The vast majority were "mosaics" – each had her or his own unique mosaic of feminine, masculine and neutral characteristics (see the table below). (Mosaicism is also characteristic of the human brain. Read more about the brain mosaic here).

Our 2015 study was conducted with three datasets of American youth. Our new dataset, which is still being gathered using the Gender Mosaic Questionnaire, includes a much larger and more diverse sample, in terms of country of origin, age, religiosity level, and sexual orientation. Preliminary analyses suggest that mosaicism is prevalent in this dataset as well.

The binary illusion

So gender characteristics rarely appear in an individual as a set of only feminine or only masculine features. Why then do we perceive humans as belonging to one of two distinct sets and fail to see their unique mosaic of characteristics? The short answer is that this happens because our society is structured around the assumption that gender is binary, that is, that individuals have either a set of feminine or a set of masculine characteristics.

This assumption is most often implicit, as in the invitation by a nursery teacher: "Girls, come listen to a story; boys, go play outside with a ball." There may indeed be gender differences in these activity preferences (with more girls than boys preferring to listen to a story, and the reverse being true for playing ball), but kids don't belong to two types: those who love stories but not balls, and those who love balls but not stories. There are also kids who love playing ball and listening to stories, and those who like neither.

These are two activity preferences, and they give rise to four different combinations. If we consider more activities, each with its own gender difference, the number of possible gender mosaics is enormous. Yet, as a result of the binary gender system, we perceive and treat others as if they belonged to one of two types, instead of appreciating their own unique mosaic of characteristics.

You can read more about the psychological mechanisms that lead us to overlook the mosaics of others and perceive them instead as either women or men, in Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain.

Gender differences in a world without gender

People often ask me whether in a world without gender there would still be group-level differences between humans with male and female genitalia. I answer that I have no clue – there may be such differences and there may not be. But I am certain that in a world without gender we simply wouldn’t care.

A gender-free world doesn’t mean that there would be no group-level differences between humans with male and female genitalia. It means that even if they existed, they wouldn’t matter to the individual. Imagine, for example, that after we’d got rid of gender, we discovered that more females than males participate in the International Mathematical Olympiad. Would we use this knowledge to discourage a maths-loving male child from studying this subject, letting him know that he is wasting his time because only a few children with male genitals manage to excel in maths in the long run? This might sound outrageous, but that’s how we commonly treat children with female genitals with respect to maths.

Note that the fact that currently we do care about gender differences is a consequence of the social importance of the sex categories, not of the existence of such differences. For example, we don’t care whether excelling in math or practicing martial arts is more common in humans with blue or brown eyes. And the reason we don’t care is not because there are many studies showing that there are no differences between humans with blue and brown eyes in these fields. We don’t care because eye color carries no social meaning. A world without gender is a world in which sex category carries no social meaning.

Comments? Questions for the author? Send to worldwithoutgender@substack.com and it may be selected for publication as part of a Conversation.

References

Bem, S. L. (1974). ‘The measurement of psychological androgyny’. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42(2):155–62.

Eliot, L. (2009). Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow into Troublesome Gaps—and What We Can Do About It. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Greenberg, D. M., et al. (2018). ‘Testing the Empathizing–Systemizing theory of sex differences and the Extreme Male Brain theory of autism in half a million people’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 115(48):12152–57.

Hyde, J. S. (2005) The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60, 581-592.

Hyde J.S., Bigler R., Joel D., Tate C., van Anders S. (2018) The Future of Sex and Gender in Psychology: Five Challenges to the Gender Binary. Am. Psychologist, 74, 171-193.

Joel, D. (2011). Male or female? Brains are intersex. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 5, 57.

Joel D., Berman Z., Tavor I., Wexler N., Gaber O., Stein Y., Shefi N., Pool J., Urchs S., Margulies D., Liem F., Hänggi J., Jäncke L., Assaf Y. (2015) Sex beyond the genitalia: The human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112, 15468–15473

Joel D. and Vikhanski L. (2019) Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain (Little, Brown Spark, New York)

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. and Stapp, J. (1975). ‘Ratings of self and peers on sex role attributes and their relation to self-esteem and conceptions of masculinity and femininity’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 32(1):29–39.

Spence, J. T. (1993). ‘Gender-related traits and gender ideology: Evidence for a multifactorial theory’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 64(4):624–35.

Tay, L., Su, R. and Rounds, J. (2011). ‘People—things and data— ideas: Bipolar dimensions?’. Journal of Counseling Psychology 58(3):424–40

Terman, L. M. and Miles, C. C. (1936). Sex and Personality: Studies in Masculinity and Femininity, 1. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Zell, E., Krizan, Z., & Teeter, S. R. (2015) Evaluating gender similarities and differences using metasynthesis. American Psychologist, 70, 10-20.