[There are]“…fundamental sex differences in the structural architecture of the human brain. Male brains during development are structured to facilitate within-lobe and within-hemisphere connectivity … whereas female brains have greater interhemispheric connectivity and greater cross-hemispheric participation....” (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014, p. 826). This citation is but one reflection of the popular belief that the brains of women and men differ in fundamental ways, and that they surely work differently. If scientific studies of gender differences in the brain are framed in this binary way, there’s no surprise that popular descriptions of such studies are often reported in the same vein: ‘The brains of men are like this, those of women are like that.’ Such reports end up giving the impression that there are two types of brains – one typical of women and the other, of men.

The problem with this way of thinking is that it applies to the brain, often implicitly, the same logic that applies to the genitals. Most humans are born with either male-typical genital organs or female-typical ones, so scientists and laypeople alike tend to assume that this binary distinction into male and female is also true of brains. Yet a careful reading of studies into sex and gender differences in the brain suggests otherwise.

First, brains of women and men are much more similar than different. For example, the conclusion cited above, reflects the finding of a significant gender difference in several dozen connections, out of over 9,000 connections assessed (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014). This is also true of gender differences in other measures of human brain structure and function (Eliot et al., 2021; Joel et al., 2015; Sanchis-Segura et al., 2019). In fact, the most prominent difference between women and men is in the size of the brain. The average brain of men is approximately 11% larger than the average brain of women (this difference is mainly attributed to the difference in body size, Eliot et al., 2021). Specific structures within the brain are also larger, on average, in men compared to women, but here too, these are mostly differences of size, not sex or gender. That is, when total brain volume is taken into account, the differences between specific measures in the brains of men and women are small and few in number. And if you compare large and small brains of individuals from the same sex category, you’re likely to find the same differences between them as between the brains of women and men. For example, large brains tend to have a higher proportion of white matter and a lower proportion of gray matter than small brains – and this is true of large and small brains of both women and men (Eliot et al., 2021; Sanchis-Segura et al., 2019; You can read more about this in a popular summary of Eliot et al’s study).

Second, even though researchers often describe gender differences in binary terms, in the relatively few measures of the human brain that do show a gender difference, there is considerable overlap between the scores in men and women (you can read more about how the size of gender differences is assessed using Cohen’s d, here[1] ). For example, in the study of connectivity in the human brain cited above, the average gender difference in the connections that differed between women and men was small, Cohen’s d = ~0.3 (Maney, 2016).

I have added to this discussion a third factor – the observation that gender differences in the brain do not add-up consistently in individual brains to create ‘male’ and ‘female’ brains. Instead, brains are most often comprised of unique ‘mosaics’ of female-typical and male-typical brain measures (Joel, 2011, 2021).

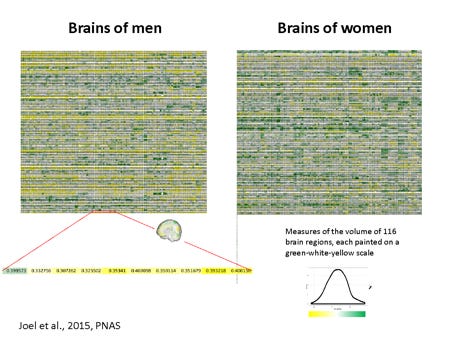

In our first study, published in 2015, we analyzed the structure of over 1,400 human brains. We found that most brains are comprised of unique mosaics of features: some brain measures (volume of specific regions, for instance) appear in a form that is more common in women compared to men, others in a form that is more common in men compared to women, and still others in a form that is similarly common in women and men. In the tables below, you can see the analysis of volumes of 116 gray matter regions in the brains of men (left) and women (right). Each line represents the volume of these 116 regions in a single brain, and the color code marks the size of each region relative to the size of this region in all other brains (of women and men combined). Green stands for larger, yellow for smaller.

At the group level, you can easily see the difference in the proportion of gray matter mentioned above: there is relatively more of it in smaller brains, which is evident in more green on the women's side and more yellow on the men’s. But you can also see that brains are rarely all green or all yellow. Rather, each brain is a unique combination of green (which is more common in women compared to men), yellow (which is more common in men compared to women), and white (which is similarly common in women and men).

In other words, what’s typical of human brains – both females and males – is to be composed of a mosaic of features. This is also true of human personalities. Each individual possesses a unique combination of feminine (i.e., more common in women compared to men) and masculine characteristics (Joel et al., 2015; You can read more about the gender mosaic of personalities in Gender Beyond the Binary, post coming soon).

Because brains are composed of mosaics of features, knowing that someone is female or male provides very little information about the structure of their brain and about how their brain is likely to compare to yours. In our studies, we showed that the chances of two people having the same brain architecture are hardly related to sex category – that is, a female and a male are nearly as likely to have the same brain architecture as two females or two males are (Joel et al., 2018). There are other lines of evidence supporting the conclusion that being female or male provides little information about one’s brain structure or function. You can read more about this in Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain.

References

Eliot, L., Ahmed, A., Khan, H., & Patel, J. (2021). Dump the "dimorphism": Comprehensive synthesis of human brain studies reveals few male-female differences beyond size. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 125, 667-697.

Ingalhalikar M., Smith A., Parker D., Satterthwaite T.D., Elliott M.A., Ruparel K., Hakonarson H., Gur R.E., Gur R.C., Verma R.( 2014). Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 111, 823-828

Joel, D. (2011). Male or female? Brains are intersex. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 5, 57.

Joel D. (2021) Beyond the binary: Rethinking sex and the brain. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 122: 165-175.

Joel D., Berman Z., Tavor I., Wexler N., Gaber O., Stein Y., Shefi N., Pool J., Urchs S., Margulies D., Liem F., Hänggi J., Jäncke L., Assaf Y. (2015) Sex beyond the genitalia: The human brain mosaic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112, 15468–15473

Joel, D., Persico, A., Salhov, M., Berman, Z., Oligschlager, S., Meilijson, I., & Averbuch, A. (2018). Analysis of Human Brain Structure Reveals that the Brain "Types" Typical of Males Are Also Typical of Females, and Vice Versa. Front Hum Neurosci, 12, 399.

Joel D. and Vikhanski L. (2019) Gender Mosaic: Beyond the Myth of the Male and Female Brain (Little, Brown Spark, New York)

Maney DL. 2016. Perils and pitfalls of reporting sex differences. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371: 20150119.

Sanchis-Segura, C., Ibanez-Gual, M. V., Adrian-Ventura, J., Aguirre, N., Gomez-Cruz, A. J., Avila, C., & Forn, C. (2019). Sex differences in gray matter volume: how many and how large are they really? Biol Sex Differ, 10(1), 32.